China‘s rush to build thousands of new museums is leading to cultural buildings “with no vision and mediocre collections”, according to architects and curators in the country (+ slideshow).

The programme, which has seen over 3,500 new Chinese museums built since 1978, has led to gigantic new institutions without exhibits, poor-quality buildings and structures located in the middle of nowhere.

“Projects have varied in scale, quality of construction, rigour of planning, and aesthetic finesse,” said Beatrice Leanza, art curator and the director of the annual Beijing Design Week event.

Private money is now pouring in to the sector, she said, augmenting projects initiated by central government, and regional and city councils willing to upgrade public facilities.

Major investors in the contemporary art field, from developers to banks and eventually individual billionaires turned collectors, have upped the numbers in the past four to five years,” she said, describing the new investors as “art patrons and nouveau-riches with a philanthropic itch, or simply a bit of an ego twist”.

Chinese architect Lyndon Neri, one half of Shanghai-based Neri&Hu, also believes that many of these buildings are the vanity projects of private investors.

“The desire to buy culture is quite rampant in China today,” he said. “Money can buy a lot of things but definitely not culture.”

nternational architects including Kengo Kuma, Steven Holl and David Chipperfield, as well as Chinese practices, have all been enlisted to contribute to this spate of new projects.

nternational architects including Kengo Kuma, Steven Holl and David Chipperfield, as well as Chinese practices, have all been enlisted to contribute to this spate of new projects.Among the projects currently under construction are Jean Nouvel’s National Art Museum of China in Beijing, an outpost of London’s V&A museum in Shenzhen, and the M+ Museum in China’s Special Administrative Zone, Hong Kong.

Many of the museums are vast, sculptural structures that take up huge swathes of land in dense urban neighbourhoods and rural areas. However, not much thought is given to what goes inside these buildings once they are complete, according to M+ curator Aric Chen.

“If you haven’t noticed, China likes to do things big,” Chen told Dezeen. “It’s all about the hardware, with scant attention given to the software.”

Neri agreed, saying that wealthy proprietors think it’s enough to build a statement building to be considered cultured, so don’t feel it is necessary to think about what is presented inside.

“The rich in this country think that by building museums, they will automatically have culture,” he said. “They do not realise that building is not synonymous to content or, for that matter, culture.”

Directives that fostered the development of a cultural economy were first set up by the Chinese government in the 1980s. These fuelled investment – both public and private – into the creative industries via two consecutive five-year plans, the latter of which ended this year. The aim was for China to have 3,500 museums by 2015 – a target it achieved three years early.

“Cultural consumption is yet another way of diversifying China’s economy from its reliance on manufacturing and exports towards domestic consumption, services, tourism, and higher-value creativity,” said Chen.

The creation of more cultural buildings also ties in with the growth of China’s middle class, who are becoming increasingly interested in art and design, and a greater interest in the country’s cultural history – which the Communist Party attempted to destroy the evidence of during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s.

“A more affluent and educated population now has more time and interest to give to cultural pursuits,” said Chen.

“When a country becomes stronger economically, it is natural for its citizen to want to go back to its roots,” added Neri. “There will naturally be a desire to understand its own identity, culture and history.”

The construction of new museums started in the larger cities, which already had established cultural scenes and a raft of institutions. The 2008 Beijing Olympic Games and the 2010 Shanghai Expo also sparked a wider construction boom, including cultural venues.

An old industrial park in Beijing was transformed into the 798 art district, with former factories and warehouses hosting galleries and studios. Elsewhere in the city, Ole Scheeren has proposed a new headquarters and museum for China’s oldest art auction house, and Nouvel’s National Museum of Art has begun construction close to the Bird’s Nest Olympic stadium.

Shanghai began heavily redeveloping its West Bund riverside as a new “creative mile” of private museums, art centres, galleries and studios for artists. The Long Museum West Bund by Atelier Deshaus and Chipperfield’s Rockbund Art Museum are both located in the area.

Provincial cities quickly followed suit, eager to cash in on the so-called Bilbao effect – enticing tourists to visit an architectural spectacle and thereby putting themselves on the map, similar to the way Frank Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim elevated the Basque city to international status.

“Smaller cities of growing ambition are seeing what’s happening in the established hubs and following their lead,” said Chen. “At the same time, the national government’s directive to build up China’s cultural infrastructure and industries extends across the country. Everyone has been feeling the pressure.”

Used as a sweetener for land deals, some museums were even built in the middle of nowhere. In some cases this was a result of bad urban planning and zoning, which resulted in the surrounding projects being abandoned.

“In China, it’s often not so much about creating a museum, with well-defined content that will attract and engage the public; it’s more about using a museum as a tool for real estate development,” said Chen.

He thinks the smaller-scale projects in rural areas are much more successful, both as structures in their context and as usual resources for the public.

“I’m seeing a lot of smaller, experimentally designed museums in rural areas that are set beautifully within their natural environments, and that in many cases really do engage their local communities,” he said.

Leanza agrees: “There are plenty of other projects realised by the likes of TAO Office, Liu Jiakun, Tadao Ando, Wang Shu, among others that might sit in lesser-known areas or with less showy collections, but truly seek engagement with their locality, cultural environment and material histories.”

“Sadly programming and contextual or social relationship is too often overridden in designs that gulp square footage with little regard for what will be housed wherein,” she said, citing the Minsheng Art Museum in Beijing as an example.

The museum, designed by local firm Studio Pei-Zhu, is housed in a former factory and includes an angular extension covered in a shiny skin of metal panels. Its cavernous interior appeared largely empty in photographs taken when it opened in September 2015.

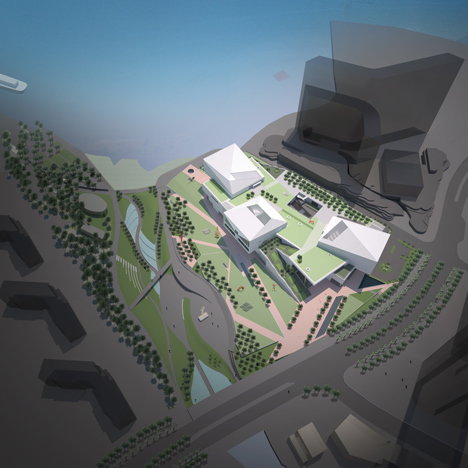

Neri thinks that Hong Kong is doing things better. Its M+ Museum designed by Herzog & de Meuron will sit on the waterfront of West Kowloon, appearing like a vertical slab balanced on another.

“If you look at M+ in Hong Kong, they are doing the right things,” said Neri, who believes that its combination of landmark architecture and a well-considered collection should provide a blueprint for similar projects on the mainland.

“The building is not even complete but the museum people in Hong Kong have already done all the ground work to focus on their collection and have all the programs planned,” he said.

The Long Museum West Bund by Atelier Deshaus and Chipperfield’s Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai, and the Ordos Museum by Beijing-based MAD Architects, are other successful examples according to Neri.

Regardless of their cultural impact, these giant projects have given international architects the opportunity to experiment while the rest of the world weathered an economic storm. But China’s economic growth is now starting to slow down, with potential implications for ambitious construction projects.

Last year China’s premier Xi Jinping also called for an end to “weird architecture” in the country. Zaha Hadid Architects director Patrick Schumacher has said that overseas firms are finding it increasingly difficult to work there.

“China is still an incredible laboratory for architecture,” said Chen. “Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t, but we’re guaranteed that something new will come out of it.”

“I don’t think architectural experimentation is going to go away any time soon,” he added. “Government projects may start holding back, but in the private sector, the genie is out of the bottle.”

HERE THE LINK: http://www.dezeen.com/2015/12/11/new-chinese-museums-construction-boom-opening-money-cant-buy-culture-china/